Valerie Campos

Valerie Campos is a voyeur of nature, a creator of scenes in which our gaze falls on a space that is composed and decomposed, that multiplies, that becomes diaphanous, abstract and figurative, timeless. It is the sublimation of the sexual; sonorous and organic, her work shows us the intimacy of the artist and a tremendous closeness to the beings (humans, animals, and plants) that surround her.

Valerie Campos: Evocations and Resonances

by Esteban García Brosseau (December, 2020)

The first thing that is revealed to the gazer when contemplating the series Resonancias, of Valerie Campos, is a formal parti-pris by which the artist has decided to distort geometrically the reality of the space that she is depicting. It is not necessary to have the certainty that this space corresponds to the actual environment where the painter lives and works, -her apartment, her studio-, because, by the mere means of painting, she evokes an intimate interior that imposes itself as her own. If it is true that the furniture, plants and canvasses that hang on the walls of this “habitat” are represented with an impeccable realism, this is not what confers them the supreme reality with which they present themselves to the spectator, but, precisely, the fact that the painter decomposes them through her skill in a certain number of transparent planes and prisms of which only the edges are visible, indicated by means of lines, generally of a clear tone. Thus, a series of surfaces and volumes, which have the coldness and transparency of glass, are superimposed in front of us, in such a way that, by one of these miracles which only good painting can produce, the everyday objects thus represented suddenly reveal us their quidditas, their that-ness, or, in other words, their own essence as existent objects situated within reality. All of this locates the spectator in a position which is simultaneously near and far from the space that has been depicted by the artist: the gazer seems to have been invited, not so much to enter the space thus revealed, but to observe it with the distance and detachment that is implied by becoming aware of it, in contrast with the general unawareness with which we generally wander in our everyday life. We are here confronted to a true “doubling of awareness”, comparable to that which, in another time and with means completely different, Velázquez was able to create with his Meninas.

This might be observed, for instance, in Resonancias, a vast canvas measuring 150 x 170 cm, which, in principle, only reproduces some furniture. We see an armchair, a sofa, and an immense jar full of flowers, -maybe asphodels-, posed in the middle of a coffee table. In the background there is a picture window similar to that of every artist studio, although this one could be mistaken with the canvasses hanged on the walls. These canvasses seem to depict a rain forest whose plants mingle with those of the apartment, thus suggesting a wild natural environment. However, the decomposition of the coffee table, fragmented in superimposed planes and volumes of white and yellow edges, brings the gazer to become aware of the reality of the space without being himself immerse in it, as if he had somehow become a voyeur of the real. However, instead of looking through a keyhole, he seems to have taken place, abandoning all guilt, behind a vast crystal, that would function as an impassable threshold. The gazer thus becomes a visitor situated in a different plane to that which is observed, a plane from which he can discover the reality of the represented space, not as it would be perceived by its dwellers, but by syntonizing himself with its resonance or vibratory frequency, as the title of the painting would seem to allude.

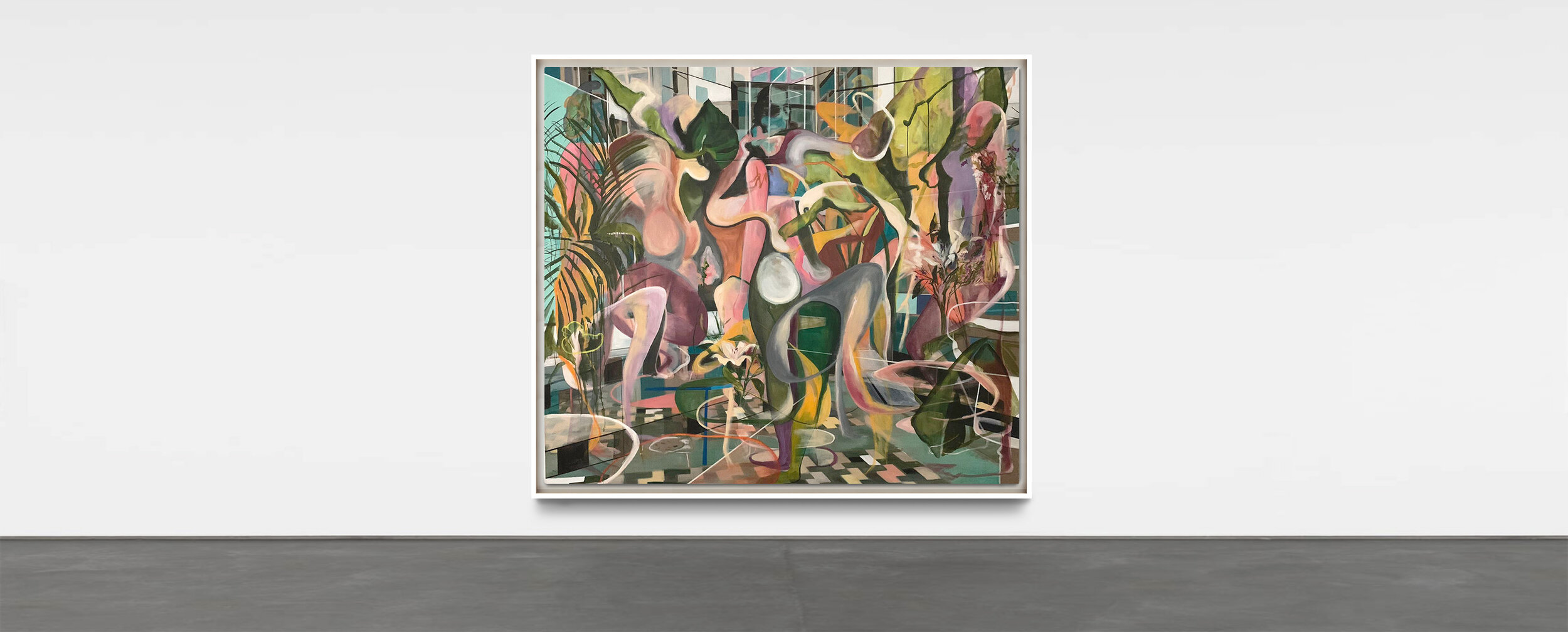

But, if the work of Valerie Campos invites us to discover her “habitat”, as it is evident in this last painting in which there is no human figure whatsoever, the role of a voyeur given to the gazer, becomes much more obvious, when, in other of her paintings, she incite us to more intimacy by revealing to us, in their nudity, the beautiful and voluptuous bodies of women of generous breast that wander through this living-room and studio, as it happens in the vast canvas Desnudo transitorio. In general, the models appear resting in armchairs or sofas as it happens with El Espejo de la transparencia. There is also a man, or at least that is what it seems, leaning confidently in a big sofa in Desnudo temporal, a much smaller canvas than the first ones, incidentally. In all of those cases, Campos recurs to the same technic of reduplication and superposition of the contours of the bodies which she has applied to the furniture and paintings of the flat or studio first described. If one may think of Duchamp (Nu descendant l’!escalier, or La mariée mise à nue par ses celibataires, même) the closest referent to this approach is certainly Picabia’s series Transparences, even if the result is completely different. Indeed, In Picabia’s paintings, the distortions imposed to the traits of his figures do not transcend the two dimensions of the canvas; they function as a closed universe that refers much more to the oneiric and the poetical than to the real. Instead, the distortions that Campos imposes to the bodies depicted, restores them to reality, of which they are a part, thus revealing us the essence of their corporality, by that same realistic magic by which she has revealed the quidittas of her material environment.

One is naturally brought to imagine, although without any solid proof, that the moment in which the models have been portrayed, took place after the consummation of the act of love, even if there is always the possibility that this impression might be erroneous and motivated only by the individual pulsion of the gazer. Indeed, the women (and perhaps one man) which are portrayed by the artist, look more like friends or even lovers, invited to participate of her intimacy, than indifferent models; the half-emptied glasses of wine and bottles of liquor that appear in Desnudo atemporal or in Desnudo transitorio seem to be testifying in that sense. The appearance of wilderness of the space depicted, mainly due to the mingling of the the plants of the studio-flat with those depicted in the canvasses that hang from the walls, evokes a Dionysian environment that tends to confirm the impression of erotic intimacy. However, here again, the word voyeur isn’t completely adequate. First, because, at the opposite of what happens, for instance, in the work of Balthus, the artist doesn’t make us participate of erotic desire at the very moment in which it arises. On the contrary, she invites us to become aware of the relaxation that it produces once it is consumed. This, very far from producing a perverse excitation, creates an effect of profound calm and confidence, that the gazer is, once more, invited to contemplate from the same distant plane, characteristic of any state of awareness, with which he has been called to contemplate the mere existence of space in Resonancias.

In Desnudo transitorio, for instance, the feminine body that occupies the center of the composition easily arouses erotic thoughts due to its movements, which accentuate the voluptuosity of her legs and breast. However, the whole is characterized by a certain feeling of tranquility and peace, accentuated by the surprising presence of a dog, that manifests his joy by synchronizing his movements with those of the model, who appears to be dancing. By being represented in time, however, the dance has blurred the face of the dancer, which is probably the same woman in panties depicted in the drawing Dancing Series. Once again, the intimacy to which the painting invites the gazer becomes evident, as it shows a space in which security and warmth predominates, and in which the models, whether feminine or masculine open themselves with complete confidence, to the generous, beneficial, and even curative hospitality of the artist and hostess, who, sometimes, has simply offered a cup of coffee or tea instead of wine and liquors as it happens in Espejo de la transparencia, a title, which expresses quite well the cold distance that separates the scene from the gazer. Incidentally, in this last canvas, beside the naked woman that is resting calmly in the sofa, there is another dog, probably the painter’s pet, whose position echoes that of the many Olmec figurines that can be seen scattered in tables and shelves.

It is probably because this pet has a great proximity to the artist, that it has been portrayed individually in Momentum. Once again one recalls here Velazquez’s Meninas, or so many other of the paintings of the Spanish master, in which dogs are portrayed as if they were members of the Royal family. However, in Momentum the pet has been depicted recurring to the same superpositions of contours used in the human models of the series Resonancias, which places it in a universe fully contemporary to ours. Among the portraits of this series Mutatio is perhaps the one that can be compared more easily to Picabia’s Transparence. It is very likely that it is a self-portrait: the model indeed, has a clear resemblance with the artist. The difference with the other portraits is that, here, the artist isn’t simply offered to the contemplation, observation, and analysis of the gazer. Indeed, her look indicates that she is herself observing and analyzing the gazer, with the same intensity with which she invites us to contemplate her intimate space. Beyond the physical likeness, this is perhaps the reason that allows us to infer more easily that what we’re seeing is a self-portrait, even if the superpositions of various faces (three of them, more precisely), could lead us to think that the artist is suggesting a sort of fusion with another woman, perhaps just another aspect of herself. On this subject, there seems to be a clear relation between Mutatio and Alma Mater. In this last canvas, the painter seems to be putting the accent in the many moods of another woman (a model, a friend, a lover?) to whom the title suggests that she has a relation of a maternal type, although her nudity would seem to indicate, as in other paintings, the moment that follows an erotic relation. Here, the gaze that the portrayed woman directs towards the gazer is completely different than that of the woman of Mutatio. Indeed, far from being analytic and inquisitive, it is mainly sweet and introverted.

Beyond the ambiguity that may subsist in this series, a painting as Evocaciones japonesas from the series Evocaciones clearly shows that erotism is a constitutive part of Campos’ work. It should be said that this series belongs to a register that is completely different from that of the later Resonancias. The paintings that belong to this series are reinterpretations of great masterpieces that have been important for the artist. In Evocaciones japonesas, for instance, Campos superposes various scenes taken from the Japanese Shunga art, which erotic register is well known, although these scenes have here lost their explicit character, for the painter has depicted them blurring them. However, it is perhaps the only painting among those that where here included in which the erotic act is represented at the very moment when it is taking place, accordingly to the characteristics of this school of oriental painting. On the other hand, the superposition of various scenes taken from the totality of Shunga art, can’t be read as if it was a series of separate events. Instead, by the recourse of superposition, the canvas becomes in its totality a single erotic interchange in which caresses and moments of ecstasy follow one another. We are seeing a precedent of the series Resonancias, for Campos has here achieved to depict in one single plane, the temporal continuum that any erotic interchange supposes, whether before or after the act of love.

The fact that in Evocación barroca, the artist has inclined herself to reinterpret elements from Velazquez’s Meninas confirms, to a certain degree, the relation that was pointed out previously between this work and Resonancias. Strangely, the effect is here completely different form that which was achieved in this last series. Instead of affirming the sense of reality that predominates, whether in the Meninas or in Resonancias, the painter gives us a subjectivist view on Velázquez, in which other references to baroque painting also appear. On the other hand, the characters depicted seem to be immerged in a Dionysian environment, more fit with the Renaissance and the Mannerist period than to the Baroque, which somehow announces the wild ambient of the studio-flat now well-known to us. Similarly, it is surprising that her reinterpretation of the Vulcan’s forge, which title is Evocación Barroca II, the bodies so precisely depicted by Velázquez, are here blurred, and interpreted so subjectively that they lose much of the realism that defines them in the original, in an opposite tendency to what is observable in the series Resonancias. While, in this last series, Campos places us in front of the quidditas of things, by offering its essence to the analytical vision of the gazer, in Evocaciones, the artist seems to have internalized the works that she has reinterpreted through a process of abstraction opposite to any kind of realism, maybe to better assimilate the world of those artists to which she felt attracted. This process of abstraction is particularly evident in her reinterpretation of Picasso’s Guernica, in which the forms of the cubist masterpiece have lost all definition, acquiring, instead, an organic and violently colored aspect that gives to it a vaguely surrealist flavor, which contrasts completely with the extremely precise intention of the cubist work of art, just as much as with the “supra-conscient” realism of the series Resonancias.

It must be said that with the series Evocaciones, Valerie Campos inscribes herself in the tradition of artistic reappropriation which is generally related to the idea of postmodernism (to which such a prosaic subject chosen for a drawing as Bath series seems to be referring), but of which, in our country, Alberto Gironella has been an incontestable precursor. Whatever the obsessions that Campos may share with this painter, whether consciously or unconsciously, and despite the distance that separates them in formal terms, one may point out the affinity that they both have for great art and Velázquez in particular. If in her process of assimilation of the great masters we can see a tendency to interiorization and of assimilative dissolution, the fact that the series Evocaciones is prior to Resonancias, shows that her reappropriation has mutated in the best of manners. Indeed, in this last series, Campos reveals her own mastery as a painter by exposing us analytically to the reality of her intimacy. This only shows us that at the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century, -a time of confinement-, not only painting has not ceased to exist, but that, far from opposing itself to the contemporary world, it is fully able to restore our sense of the present. To recur, - by distorting it, of course-, to an old expression that yesterday critics used to consecrate painters whose importance had become irrefutable, we may say that Valerie Campos has found herself again, - and not only found herself-, as a painter.